Photo Gallery String Gauges and Tunings Specifications Home

Photo Gallery

String Gauges and Tunings

Specifications

Home

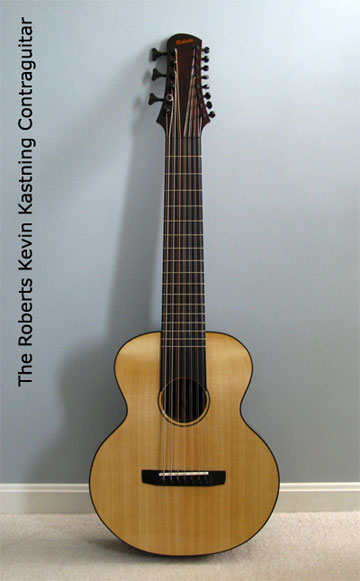

UPDATE: November 2012: Contraguitar C1

has been back to Dan Roberts and is now a

17-string

Contraguitar. Dan added a high D double-course above the high A

course, and a single-course low B below E. More photos and info coming soon.

The Genesis

My passion for extended-range instruments, and the causality for them

can be found here. And here.

And here. The Contraguitar was born out of a need

for a dual-course instrument which encompassed the range of a bass, the extended baritone

registers, and even covered some of the lower alto registers. Around the

time of the recording sessions for the album that would become

Resonance, I began to consider an extended

baritone-type instrument, but with an extended upper register. I had been

discussing an extended range, short-scale guitar with Santa Cruz Guitars for a

couple of years; this instrument would come to be known as the KK-Alto guitar. By this

time, the KK-Alto guitar was in the works, yet I had

something in mind for compositions I was hearing in my head and starting to

write, but for which no

instrument existed. I knew it could not be a 6-course instrument, but more

likely a 7- or 8-course instrument. Since its arrival in 2006, the Santa

Cruz DKK-12 had become my main instrument. I had

also been working extensively on classical guitar, and its wider neck and string

spread allowed me to imagine and execute concepts and ideas which were not

attainable on the DKK-12; hence, this instrument would require a much wider

fingerboard with a classical string spread. After the release of

Resonance in 2007, I couldn't stop thinking

about this new instrument. The instrument began to take shape in my mind,

and I tried to categorize it in my thoughts; it wasn't another baritone or

extended baritone. The name I settled upon would assist in explaining and

categorizing the

entire concept. At the same time, I was composing a chamber piece which

included bassoon. I had been reading a book which lived on my desk, Walter

Piston's

Orchestration, about the registers of both bassoon and

contrabassoon;

contrabassoon being one octave lower than the bassoon. Since this

instrument would be an octave lower than guitar, the "contra" prefix really

stuck in my head.

After a few days, I called my friend Dan Roberts at the Santa Cruz Guitar Company (SCGC). Because I am an artist endorser for SCGC, they had always been very supportive of my music, and had enthusiastically created the atypical instruments I had conceived. Dan and I had worked on several instruments together, and I credited Dan with being the driving force responsible for bringing to life the other KK series instruments: the DKK, the DKK-12, and the KK-Alto guitar. I explained to Dan what I had in mind; the range, registers, and number of courses. I explained the classical string spread, and some other details. I then held my breath and asked Dan if he thought such an instrument would even be physically possible. He asked me some questions about string gauges and scale length, and then replied that it should be possible. Dan asked what I was going to call it. I said, "The Contraguitar." He asked how I'd selected that as a name; I told him about bassoons and contrabassoons; he decided it was a pretty accurate name. Dan and I set about the long and arduous task of defining the specifications. This instrument was going to be far more of a challenge than any of the other KK series instruments. At every turn, I was braced to hear Dan say that this bizarre instrument just wasn't going to work. Fortunately, that declaration never came.

Taking Shape

When I began speaking with Dan about it, I had

specified the 12-fret D body which we had used to great success with the

DKK and the DKK-12. It

was up to me to determine things like the nut width and the string spread at the

bridge, two of the most critical dimensions of the entire instrument.

Everything else would be based on the scale length and the nut width: bridge

location, soundhole placement, neck-to-body joint fret number, top voicing and

bracing, and more. No work could begin before these measurements were

determined. Before I could determine these key measurements, I had to

settle on the number of courses and strings for the Contra. Originally, I

had thought of going with either 15 or 16 strings, but both in an 8-course

scenario. If it were 15 strings, the low E would be a single course, while

all others would be double courses. I had also considered the possibility

of either 14 strings in 7 courses, or even 18 strings in 9 courses. I ran

all the possible scenarios past Dan, again to see if they would be possible.

Dan stated that given what we had already determined, that the number of strings

would really be determined by my technique, ability and comfort. I spent

months making cardboard fingerboard mockups of various widths and tapers for

each stringing scenario, to determine just how wide and possible each one might

be. And to determine the limits of what would be possible to fully utilize

when playing.

I enjoy pre-baroque and baroque lute composers. Possibly my favorite lute composer is Sylvius Leopold Weiss (1686-1750). I had been listening to Weiss extensively during the period I when I was designing the Contra, and may owe some of its development to his spirit. Weiss was a very prolific composer, leaving over 600 works for lute. One of Weiss' major achievements was the expansion of the lute itself, as he expanded it into a 13-course instrument. And then went on to compose pieces specifically for this expanded instrument. However, in the world of the multi-course lute, some of the bass strings are meant as continuo courses, meaning that these strings are not to be fretted, only played open. In fact, on Weiss' lute, the lower bass courses are suspended over the fingerboard and cannot be stopped at all. While I did plan on a multi-course Contraguitar, I did not plan on any of the strings being used as continuo strings; everything would be over the fingerboard, and all strings would be used equally in all positions. This meant that the fingerboard could be no wider than I could comfortably play and reach. That would determine the number of courses. I had also been playing an 11-string Altengitarre, which is a short-scale 11-course classical guitar, tuned to G above E, and is mostly utilized for lute transcriptions. The nut width on the altengitarre was 3.75 inches (96 mm). The altengitarre's five bass courses, while over the fingerboard, were not originally intended to be stopped or fretted, but used as continuo strings, and played open. I could reach the lower bass courses and use them as fretted notes, but it was not comfortable; the reach was enormous. Were the Contra to be a 16-string/8-course instrument, the nut width would be have to be as least as wide as the altengitarre. This would relegate the lower courses to defacto continuo usage, and this is not what I had in mind. I made yet another cardboard fingerboard mockup of a 14-string/7-course example, which utilized a 3.25 inch nut width (83 mm). The overall nut width was based on the spacing at the nut of a classical guitar; by duplicating the spread at the nut on a classical, the nut width for the Contra would be automatically determined. While extremely wide, this did feel possible, and the reach to the lower registers was quite possible. In late winter of 2010, I called Dan, and gave him the final decision: the Contraguitar would be 14 strings in 7 courses.

String Theory

After I had finalized the scale length and the nut and bridge dimensions, the

next point of impact we had to determine was strings. String tension would

be a larger-than-usual factor on the Contraguitar, as the bracing would be

tremendously impacted by this increased string tension. To determine just what the bracing would be, Dan

and I both poured over the

D'Addario string tension charts for weeks. Discussions went back and forth, as

we both did our research to determine string gauges. For a starting point,

I began with the gauges I'd been using on the DKK-12.

However, the DKK-12 has a scale length of 28.5 inches (724 mm); the Contra would

be 30 inches (762 mm). The scale length would have an additional impact on string

tension, and again, serve to help determine the bracing patterns. We

needed to take into account varied elements such as guitar strings versus bass

strings; some bass gauges can be found in guitar strings, and some guitar gauges

can be found in bass strings. Besides the scale length, we had to decide

if there was a difference in string tension, as bass strings in the same gauge

as a guitar string (for example, .066 is available in both guitar and bass) can

have different core size, different wrap sizes, differing number of layers of

wrapping, as well as different wrap materials and wrap compounds (nickel,

stainless steel, phosphor bronze, 80/20 bronze, and more). Even the

core shape (round or hexagonal) has an impact. All variables would have an

effect on the overall string tension. Differing string types would also

have a direct and profound impact on voice, volume, responsiveness, and playability.

Dan and I discussed strings for a couple of months or more. Eventually, I

devised a starting point for our set of Contra strings, and ran it past Dan to

get his blessing. He approved, and another piece of the puzzle was in

place. If you look closely at the Contra photos, you'll notice that I'm

using a mixed set of strings including nickel, phosphor bronze, and 80/20 bronze windings. The

different materials over an instrument with such a wide frequency range actually

provides a very tonally balanced and responsive voice. Mixing windings on

a concert 6-string would not result in a homogenous voice; yet on the Contra,

the opposite is true. I specified that the bridge would use all

guitar-sized pins, not bass pins. This meant that the bass strings could

not be top-loaded, like guitar strings, but would have to be loaded from the

inside. Bass pins would have pushed the octave string too far away from

the diapason string to be usable; the exaggerated gap would have rendered the

bass courses impossible to use as dual-courses. Dan accepted the

unorthodox bridge design, and devised an elegant bridge which performs exactly

as I had hoped.

Under Construction

Around the time that the specifications for

the Contraguitar were finalized, Dan left SCGC to start his own guitar company,

Daniel

Roberts Stringworks. Because Dan had been so intimately involved with

all aspects of the Contra, and had been the luthier that voiced

and helped create the other three highly successful KK series instruments, I

felt strongly that I wanted him to see it through, and I trusted Dan to take

over the creation and realization of the Contraguitar at the new stringworks.

I had specified cocobolo rosewood for the back and sides, and Carpathian spruce

for the top. This combination had provided a beautiful, resonant, and

balanced voice on the DKK, and with such a wide and demanding range for the

Contra, I knew it would be ideal. Dan agreed, and set about finding the

perfect sets. Originally, I had settled on the 12-fret D body, but now

that the scale length and nut and bridge widths were finalized, Dan suggested

that a body based on a Gibson J-200 might be better suited for this massive

instrument. The J is much larger than the D, and with such a bass-register-oriented

instrument, all that extra internal volume of space would certainly be ideal.

I have always found the J bodies to be very comfortable, so I agreed.

Most of my other instruments have cutaways. I didn't want a cutaway on the Contra, due to the attempt at maximizing internal space/volume of the body. I asked Dan if such a longer scale length would allow for a 15- or 16-fret neck. Most guitars have either a 12- or 14-fret neck; this is the fret number wherein the neck and body meet. Moving the neck joint out to 15 would provide increased access to the upper registers without the need for a cutaway. Dan's final design did in fact allow for a 15-fret neck design. I specified that everything above the 17th fret was to be fretless. I do a fair amount of fretless work, and on the KK-Alto guitar, I had done the same design, reserving the upper register as fretless, and it had proved to be very useful to me. On an instrument utilizing bass strings, a fretless region would be wondrous.

Once we had the body design and neck length and width selected, it was up to me to work with Anvil Cases to spec and order the case for the Contra. Being such an unusual instrument, there were no cases which would even come close to fitting it. Spec'ing out a case for something which doesn't yet exist is not an insignificant task. I had worked with Anvil on other cases, and they had proven to be a good partner for odd-sized cases. Not only that, but Anvil sets the standard for durable touring cases, a critical factor when touring in other countries. By early August 2010, the case was complete, and on its way from Anvil in California to the Stringworks in Montana.

Specifications and Details

The tuners presented another challenge. We

couldn't use just one type; the wide variance of string gauges prevented that.

The Contraguitar would be using both bass and guitar strings at the same time.

Bass tuners would be required. For the bass tuners, I selected the

Gotoh

20:1 bass tuners. Another consideration is the fact that we would be using

guitar strings, which are made to fit instruments with scale lengths of around

25 inches on a 30-inch scale instrument. I was concerned that there could

be problems with the guitar strings being too short, and not having enough wraps on the tuning posts to keep the

instrument in tune, due to the strings being less than an optimum length; not to

mention the length of the extended headstock. Such a large headstock would

put some of the tuners around eight inches away from the nut. The idea

occurred to me that locking tuners for the guitar-gauged strings would work

beautifully, as locking tuners don't require wraps on the post, but actually

"lock" the string end into the tuner. I have been very fond of the

Grover vintage

re-issue "Sta-Tite" 18:1 tuners, using them on several of my instruments.

I discovered that Grover used the same tuning ratio in their

Rotomatic

locking tuners. And, since the locking Rotomatics were available as

"mini" sized, allowing for the closer tuning machine placement we had designed. I selected

those for the guitar gauge strings. While that was one problem solved, I

was concerned about tuning difficulties on the bass side of the headstock.

Would it be nearly impossible to reach around and between the large bass tuners

to grasp the smaller guitar tuners for the bass octave strings?

Would tuning one of the bass octave strings cause collisions with the larger

bass tuners, thus rendering the tuning process frustrating, if not impossible?

I started to think about tuners which would not be accessed from the same angle

as the bass tuners. It would require something unusual. I decided on

the

Steinberger tuners. The Steinbergers are accessed from the back, not

the side. Plus, as a bonus, they are also of a locking design, so that

solved the issue of the bass' octave strings possibly being too short.

As for the tonewood sets, finding the right sets for a given instrument can take months. When Dan set out to build my SCGC D back in 2000, the search for the ideal cocobolo rosewood back and sides set took over eight months. With such an unusual and demanding instrument as the Contra, I was ready to wait at least that long once more. However, Dan informed me that he had a wonderful and very dense set of cocobolo which he'd had for years. He had never selected it for any of his instruments, as the fundamental tap tone was unusually low, further down in the bass register than any other cocobolo set he had experienced. Dan felt quite strongly that this set would be perfect for the Contra and its extended bass registers. Not long after he had informed me of the cocobolo discovery, Dan called to say that he also had the top set. Dan had a set of very old Carpathian spruce; again, another set he had had for years. The coloring wasn't what most people would deem as cosmetically perfect, but the grain width and cross-grain stiffness was exceptional; in fact, Dan stated that this was the stiffest Carpathian set he'd ever experienced. As such, he had set it aside years ago for a special instrument, and now, years later, the Contra was it.

While on the 2009 European Tour for Parabola, my guitars were amplified by microphones; one external (Shure KSM-44), and one small internal mic. None of my instruments had the small internal pickup or mic, so Sandor had loaned one to me. I wanted to address this issue during the build of the Contraguitar, as I knew I would be touring with it. I've never liked the sound of pickups, so I set out to research a small internal mic. One which would not be a pickup, but an actual microphone, and one which would not impede the instrument in any way. I settled on the GHS mini-flex microphone, which Dan installed during the build process. If you look closely in the photos, you can get a glimpse of it inside the soundhole.

Since I had been playing so much classical guitar, I specified for the fingerboard to be flat, like that of a classical. This was just about unheard-of for a steel-string instrument, as they always have a radiused fingerboard. A flat fingerboard would also impact the bridge design, as the top of the bridge would have to be flat, like the bridge of a classical. To further complicate matters, I specified a 1/4" bridge saddle width. This was to provide two allowances: first, to create plenty of topographical bridge saddle area so that having enough space for correct intonation compensation would be assured. Second, I had an idea to use a pair of 1/8" saddles; one carved for proper intonation of the root (diapason) strings, which would remain a constant. The second 1/8" saddle would be carved for the intonation of the various intervallic tunings I employ; a different secondary saddle for each tuning scenario. I carve my own saddles, so this would allow extremely accurate intonation, regardless of the tunings.

Due to the extended width of the fingerboard, and thus the neck, I wanted a neck profile which was as flat as possible on the back. Most necks are either round in a D- or C-shape, or angled in a V-shaped on the back, but doing so on the Contra neck would serve increase the distance the left fingers are required to span. Making the neck profile flatter would allow for more reach, and would be more comfortable in this situation. Dan agreed, and said that a flat neck profile would be no problem to carve. After additional time spent with the altengitarre, I proposed to Dan that we design the neck profile to be asymmetrical. I'd never heard of this being done, but my logic was that if the back of the neck was thinner under the treble side, this would increase reach even further. Fortunately, Dan agreed. To ensure stability in such a massively wide and long neck, we had originally considered a double-truss rod system. However, as time went on, and we determined the tuners and other components, Dan begin to be concerned that double truss rods would make the instrument neck-heavy and upset the playing balance. I suggested the somewhat new concept of embedding carbon fiber rods in the neck. Carbon fiber is as rigid as steel, but very lightweight. Dan thought it was a great idea, so I had two rectangular carbon fiber rods shipped to his shop. The pair of carbon fiber rods and Dan's selection of a double-action single truss rod has made for an incredibly stable neck.

Dan's Approach

As the project began, Dan kept a

photo journal of each phase of the build and design process on his

Facebook page. Dan had this to say: "This will be a photo essay on the

design, and building of a 14 string Contra Guitar. It will range from possibly

as low as B, a fourth below the bass E, through bass registers and baritone

registers, most pitches being strung in octave courses, to learn it and then in

Kevin's own intervallic tunings after he is accustomed to it. See the Photo

Album on Kevin Kastning to learn more about the Artist I am building it for. He

is an important figure in modern composition and especially guitar composition.

He has collaborated widely with the likes of Hungarian multi string virtuoso

Sandor Szabo, and Sting's co-writer and guitarist, Dominic Miller. Watch the

evolution of an instrument that has never before existed and will require a

monumental talent on the level of Kevin Kastning to give it musical life and

expression! As Kevin states below, He will initially tune the Contra in

octaves as he learns the new instrument but then will begin to tune the courses

in intervals allowing him to play 14-note chords. (for perspective, think 4

hands on a piano!) Imagine the orchestral possibilities of this

instrument." Dan later stated, "I would never consider building such a

demanding instrument for anyone other than Kevin Kastning." See

Dan's Facebook photo essay for complete build photos; as well as Dan's

running commentary and narrative at each phase of the project.

The Realization of a New Voice

Dan got to spend a few days with the Contra in a completed state. He spent

time playing and testing it, and said, "When it was finally finished, I was in

for a pleasant surprise. Not only did it have a nice complexity and organized

overtone series but the top showed very little distortion from the increased

tension and the treble response was wonderful. It has really good sustain all

the way up the neck as well. I found myself mesmerized by this instrument.

I just sat engrossed as I sampled the incredibly wide range of this instrument.

It has a nice roundness of tone with a good separation and wonderful clarity."

In

early September 2010, a huge and very heavy FedEx shipping container arrived.

Inside was the Anvil case safely cradling the KK Contraguitar. To finally

see and hear something which was over three years in the making was immensely

gratifying. I knew that Dan would be the only person I would trust with

bringing such a bizarre instrument to life. Not just making it, but

ensuring that it had a fully balanced voice in all registers. This is

something I had stressed to Dan that would be critical for the Contra, and I

knew he could do it, as achieving a balanced voice is something in which Dan

excels. While I was confident he could do it, there was still a tiny

element of questioning if balance in an instrument which was really covering the

ranges of three other instruments was a realistic goal. The laws of

physics still apply to instrument making; would a responsive treble register in

an extended J type instrument still be possible? Dan kept pretty

quiet about the final voice and sound, but then he always has in our instrument

collaborations. He never wants to set unrealistic expectations; nor

pre-bias me for or against anything. After a few chords and scales played

on the Contra, my concerns melted away in the huge rumbling voice of this

instrument. It was very balanced across all registers, just as I had

hoped. I spent a full day with it before calling Dan with my review.

When I did call him, he was excited and I think even relieved to hear how happy

I was with it. He then told me that he was extremely pleased and excited

at the final result.

In

early September 2010, a huge and very heavy FedEx shipping container arrived.

Inside was the Anvil case safely cradling the KK Contraguitar. To finally

see and hear something which was over three years in the making was immensely

gratifying. I knew that Dan would be the only person I would trust with

bringing such a bizarre instrument to life. Not just making it, but

ensuring that it had a fully balanced voice in all registers. This is

something I had stressed to Dan that would be critical for the Contra, and I

knew he could do it, as achieving a balanced voice is something in which Dan

excels. While I was confident he could do it, there was still a tiny

element of questioning if balance in an instrument which was really covering the

ranges of three other instruments was a realistic goal. The laws of

physics still apply to instrument making; would a responsive treble register in

an extended J type instrument still be possible? Dan kept pretty

quiet about the final voice and sound, but then he always has in our instrument

collaborations. He never wants to set unrealistic expectations; nor

pre-bias me for or against anything. After a few chords and scales played

on the Contra, my concerns melted away in the huge rumbling voice of this

instrument. It was very balanced across all registers, just as I had

hoped. I spent a full day with it before calling Dan with my review.

When I did call him, he was excited and I think even relieved to hear how happy

I was with it. He then told me that he was extremely pleased and excited

at the final result.

The physical size of the Contraguitar is tough to visualize without a comparison. Here it is next to my SCGC D, and here it is beside my Cervantes classical.

As of this writing, I've only had the Contra here for a couple of weeks, but I can't put it down. The voice is massive; yet balanced. The sound just seems to come from everywhere; the volume is loud and enormous. The action is very comfortable all the way up the fingerboard. It is entirely a new instrument, and one which requires the approach of learning a new instrument. Already I have begun to change and adapt techniques to work with it; as well as finding entirely new techniques. I look forward to continuing to learn it, and to learn from it.

To Dan, my sincerest gratitude.

-Kevin Kastning

September 2010

Roberts KK-Contraguitar photo gallery

[file:///C:/Websites/Kevworld/photogallery/photo00028145/real.htm]

17 strings

Cocobolo rosewood back and sides

Carpathian red spruce top

3.25 inch nut

(82.5 mm)

30 inch scale (762 mm)

Figured cocobolo rosewood headplate overlay

All maple/dyed maple purfling and rosette

Bracing/voicing: double-tapered, highly knifed, scalloped tonebars

Mahogany neck

Ebony fingerboard and bridge

Bone saddle

Ebony nut and unslotted bridge pins

Tuners:

Gotoh compact bass (3)

Steinberger (3)

Grover locking mini-Rotomatics (8)

B (bass) thru D (alto)*

Tuning (bass to treble):

B

E/e

A/a

D/d

G/g

B/b

E/e

A/A

D/D

*This is the octave tuning; I will be using

many intervallic tunings, such as the DKK-12 examples on

the tunings page.